Problems With Volume Of Commerce In Antitrust Sentencing

By Robert E. Connolly and Joan E. Marshall

Law360, New York (September 15, 2014, 10:28 AM ET)

The recent sentencing of Mathew Martoma for insider trading focused the debate over the severity of white collar crime sentences driven by mechanical calculations in the federal sentencing guidelines. The probation department had recommended 20 years in jail based on the fraud guidelines profit calculations. Martoma was sentenced on Sept. 8 to nine years in prison.[1] Last month the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which sets the federal guidelines, announced it was considering changes to its policies on white collar sentences, specifically addressing the issue of profit and considering whether “there are ways the economic crime guidelines could work better.”[2] While profit is certainly a factor in sentencing, the steep and severe sentences based on profit calculations are under question.

____________________________________________________________________

Subscribe to Connolly’s Cartel Capers Blog Here

____________________________________________________________________

Even more questionable, however, is the antitrust sentencing guideline U.S.S.G §2R1.1, where individual jail sentences are swiftly driven upward to the Sherman Act 10-year maximum, not by any defendant’s personal profit, but by the volume of commerce.[3] The volume of commerce is the most significant upward adjustment and can more than double the base offense level of 12. The relationship between volume of commerce and culpability is at best tenuous. The weight placed on the volume of commerce in calculating prison sentences has led to great uncertainty, departures by judges in contested sentences, and routine departures by the Antitrust Division in plea agreements.

In this article, we look at the defects in using volume of commerce as a significant component of determining prison sentences for individual antitrust defendants. We also recommend reforms that would insert more meaningful measures of culpability into the sentencing process.

The Guidelines Volume of Commerce Is Not a Reasonable Measure of Individual Culpability

Due to the weight given volume of commerce, a defendant with no prior criminal history in an international antitrust cartel can find himself close to 10-year Sherman Act maximum regardless of his role in the offense. The volume of commerce can add up to 16 levels to the base offense level of 12. An offense level of 28 results in a guidelines calculation of 78-97 months in prison before any other adjustments. While Congress did raise the Sherman Act maximum to 10 years, maximums are only appropriate when there are aggravating circumstances — not for a typical, but large cartel. While unintentional, in practice the guidelines harshly punish foreign executives since the most severe penalties are reserved for international cartels with large volumes of commerce.

There is little correlation between the volume of commerce in a cartel and individual culpability. For example, an owner of a concrete company that rigs bids on $5 million worth of contracts on public projects and personally pockets the conspiratorial overcharge is more culpable than a lower level employee in a $1 billion international cartel that is ordered to attend cartel meetings. Yet, the concrete company owner would get a two-level upward adjustment resulting in a guidelines range of 18 to 24 months while the lower level employee in the international cartel would get a 14-level adjustment and be facing close to the Sherman Act maximum of 10 years. These are not extreme hypotheticals — they are essentially the guidelines results in United States v. VandeBrake[4] and United States v.AU Optronics.[5]

In VandeBrake the court departed upward from the guidelines and imposed a four-year sentence on the concrete company owner. In AU Optronics several lower level executives were acquitted, but even the president and vice president received downward departures to sentences of three years. When rejecting the government’s 10-year guideline prison recommendation in AU Optronics, the court said, “The defendants thought they were doing the right thing vis-a-vis their industry and their companies. They weren’t, but that’s what they thought at the time.”[6]

On the other hand, the judge in VandeBrake found the defendant was motivated by greed. The commentary to the antitrust guidelines states: “The offense levels are not based directly on damage caused or profit made by the defendant because damages are difficult and time consuming to establish.”[7] While a blunt proxy like volume of commerce may be suitable for assessing a corporate fine, when individual liberty is at stake, more relevant culpability factors are needed.

There is another major flaw in the application of the volume-of-commerce adjustment to individual sentences. Under U.S.S.G. §2R1.1 (b)(2), “the volume of commerce attributable to an individual participant in a conspiracy is the volume of commerce done by him or his principal in goods and services that were affected by the violation.” This means that if the CEO of Company A decides to form or join a cartel and at the same time directs his sales manager to coordinate price and volume data with competitors, both are tagged with the same volume of commerce. This isn’t right.

There used to be a principle of big fish/little fish by which prosecutors and courts differentiated between the role a person played in the offense, including seniority, motivation for, and benefit received from the crime. Cartel members themselves make this distinction, often referring to cartel meetings as “top guy” or “working group guy” meetings. But, the volume-of-commerce adjustment contains no such distinction. The guidelines do provide for a mitigating role in the offense adjustment, but in an antitrust case, this makes only a slight difference in the recommended guidelines range.[8]

There are two other drawbacks with using the volume of commerce to determine an individual’s jail sentence. First, the volume of commerce is usually determined through very lengthy and complex negotiations between the Antitrust Division and the corporate defendant. The negotiations cover variables such as the duration of the conspiracy, the geographic scope of the conspiracy, the products involved and the customers affected.[9] An individual defendant is often later sentenced using a volume of commerce he had no input in calculating and insufficient resources to challenge. Finally, courts have taken an expansive view of what commerce should be included in the guidelines calculation. Courts have uniformly held that all sales made by a defendant corporation during the price fixing conspiracy should be presumed affected by the conspiracy.[10]

Some Suggestions for Reform

1. Reserve the Sherman Act Maximum for Egregious Cases

The maximum prison sentence of 10 years under the Sherman Act should be reserved for the most egregious cases.[11] These cases would include aggravating factors such as recidivism, economic coercion of competitors or subordinates to join the cartel, or extraordinary steps to prevent detection or reporting of the cartel.

2. Increase the Base Offense Level

Rather than adjust the offense level dramatically based on volume of commerce, we suggest that the base offense level be raised to a level 17 with a resulting sentencing range of 24-30 months. This captures the philosophy that short but certain jail sentences are crucial to deterring antitrust crimes — with “short” being redefined in light of the increase in the Sherman Act maximum to 10 years in jail. The recommended guidelines prison sentences should begin within this range, but allow for more culpable senior executives to face longer jail sentences based on enhancements.

3. Eliminate Volume of Commerce Except for the Most Senior Member of the Conspiracy

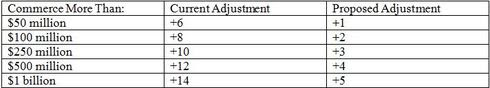

If the volume of commerce has a relationship to culpability, it should be limited to the senior executive responsible for engaging the company in a cartel. Even here, however, we would limit the extreme sentences for large international cartels by lowering the upward adjustment for individuals.

While not related to volume of commerce, we propose eliminating the aggravating-role adjustment for the number of participants in the offense. U.S.S.G. §3B1.1 provides for an up to four level enhancement if the conspiracy involved five or more participants. There should be no enhancement based on the number of participants in the cartel. It is simply double counting. By their very nature, price fixing cartels involve numerous participants. Participants in smaller antitrust cartels are not more or less culpable than individuals in larger industries.

5. New Enhancements Should Be Added to the Guidelines Based on Individual Characteristics

To compensate for eliminating or reducing the role of the volume of commerce adjustment, the base offense level could be increased by a rage of one to four levels if the court finds that the defendant was motived by personal gain in the form of increased salary, bonuses or stock options. There is no difference in liability if an agreement was reached to try to prevent layoffs in a distressed industry, as opposed to increasing prices to boost stock options or pay, but there is a difference in culpability.

Courts will consider these factors whether they are mentioned in the guidelines or not, so to maintain some consistency, some sentencing discretion should be added based on these factors. Other personal characteristics, such as whether the defendant helped initiate the cartel or ordered subordinates to participate, are also relevant to culpability and should be taken into account by the guidelines.

6. Add an Enhancement for Failure to Have an Effective Antitrust and Ethics Compliance Program

While not related to the volume of commerce, we suggest a revision to encourage strong and effective ethics and compliance programs. The Sentencing Commission should consider enhanced punishment for any individual defendant who was in a leadership position and failed to implement a compliance program as set forth in the Sentencing Guidelines. U.S.S.G. §8B2.1(b) lists the seven factors that must exist for a compliance and ethics program to be considered “effective.” A senior executive who had the authority to implement, or at least advocate for an antitrust compliance program (typically c-suite executives) and failed to do so is more culpable than an executive who violated a compliance program. These executives fail to give their subordinates the training they need to identify and resist involvement in the criminal activity and fail to inform them of the “whistleblower” mechanisms available to stop the activity.

This proposal is based on our collective experience in sitting across the table from lower level foreign executives who have only a vague notion about the U.S. antitrust laws and do not have an appreciation for the consequences of what they are being told to do by their superiors. Antitrust and ethics training can reduce the incidence of these scenarios.

These Suggested Reforms Will Benefit Antitrust Enforcement

These reforms are not suggested to go “soft” on criminal antitrust offenders. As former career Antitrust Division prosecutors, we have urged courts to imprison convicted antitrust defendants. We don’t presume to have all the answers on antitrust guidelines reform, but we think we have identified the most pressing issue. As the Sentencing Commission reviews the antitrust guidelines, we urge that consideration be given to reforming the way volume of commerce escalates an individual’s recommended prison guidelines range.[12] When an individual’s liberty is at stake, it is important to get it right.

—By Robert E. Connolly and Joan E. Marshall, GeyerGorey LLP

Robert Connolly is a partner in the Washington, D.C., office of GeyerGorey and former chief of the Middle Atlantic Field Office of the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division. His blog, Cartel Capers, covers price-fixing, bid-rigging and market-allocation issues. Joan Marshall is a partner in the firm’s Dallas office and a former trial attorney for the Antitrust Division.

The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the firm, its clients, or Portfolio Media Inc., or any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.

[1] See http://www.law360.com/

[2] See Christopher Matthews, September 7, 2014, at http://online.wsj.com/

[3] “For purposes of this guideline, the volume of commerce attributable to an individual participant in a conspiracy is the volume of commerce done by him or his principal in goods or services that were affected by the violation.” U.S.S.G §2R1.1 (b) (2).

[4] United States. v. VandeBrake, 771 F. Supp. 2d 961 (N.D. Iowa 2011).

[5] United States v. AU Optronics Corp. et al., CR-09-0110 (SI)(filed June 10, 2010).

[6] United States v. AU Optronics Corporation, CR-09-0110 (N.D. Cal. Sept 20, 2012)(sentencing hearing).

[7] U.S.S.G. §2R1.1 application note 3.

[8] See Mark Rosman and Jeff VanHooreweghe, Antitrust Source, August 2012 “What Goes Up Doesn’t Come Down: The Absence of The Mitigating Role Adjustment In Antitrust Sentencing, available at: http://www.wsgr.com/

[9] The many variables subject to negotiation are outlined in the Antitrust Division’s Model Plea Agreement. See Antitrust Division Model Annotated Corporate Plea Agreement, available at: http://www.justice.gov/atr/

[10] See e.g., United States v. Andreas, 216 F.3d 645, 678 (7th Cir. 2000); United States v. Hayter Oil. Co, 51 F.3d 1265, 1273 (6th Cir. 1995).

[11] Although Congress raised the Sherman Act maximum prison sentence to ten years to indicate the seriousness of antitrust offenses, it is still true that some offenses are more egregious than others and the maximum penalty should be reserved for such cases.

[12] For a more detailed look at suggested reforms to the antitrust guidelines for sentencing individuals, see Letter of Robert E. Connolly to the Sentencing Commission, July 29, 2014 available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/